Manoomin gii-nitaawigiyaan Makak, sensor for manoomin

June 1, 2024

Read the article here on page 8 of Mazina'igan - A Chronicle of the Lake Superior Ojibwe

By Bay Paulsen, Staff Writer

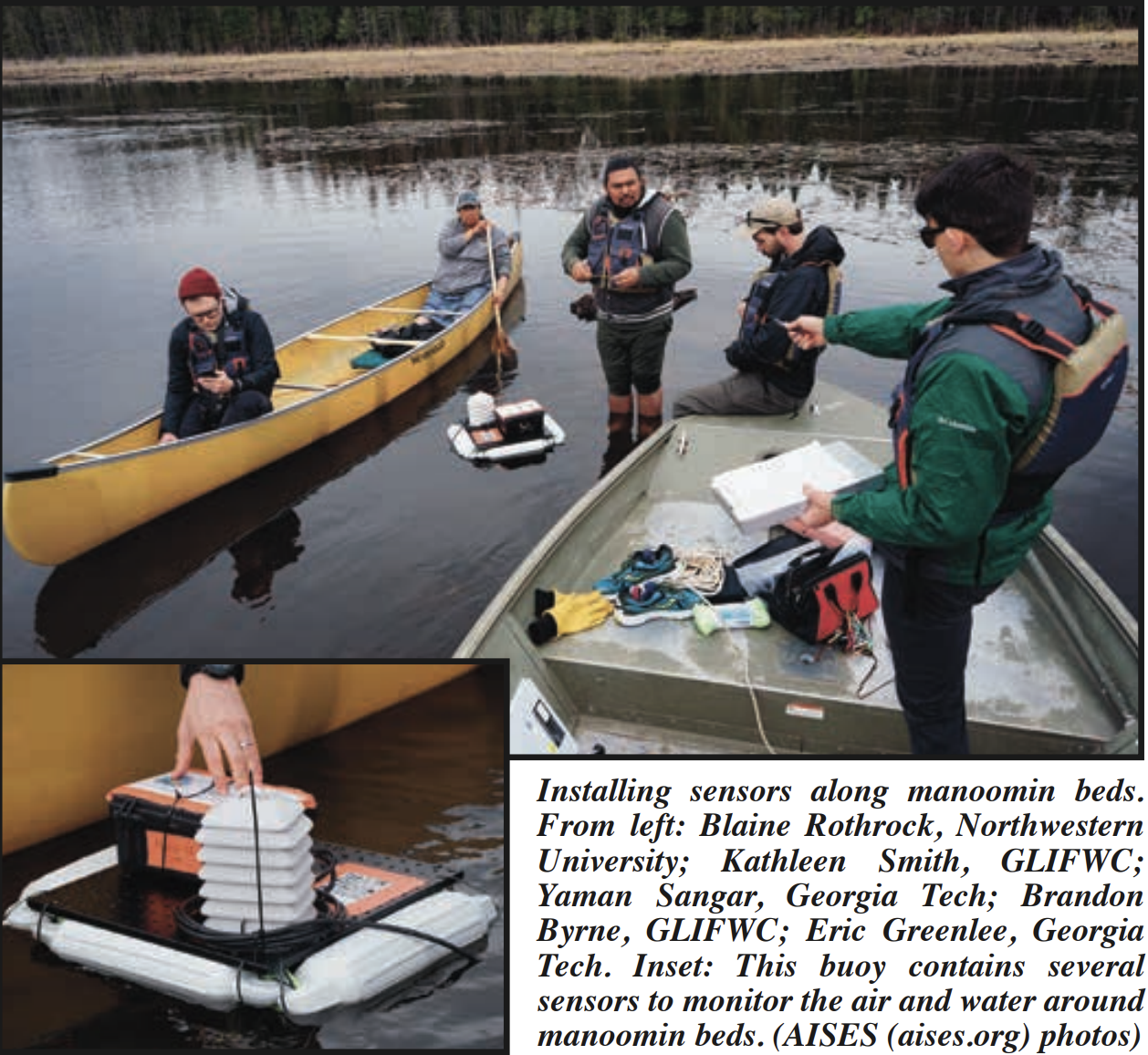

If manoomin (wild rice) plays a role in your life, whether you’re harvesting it to feed your family, hunting waterfowl in the fall, or simply observing its life cycle as it grows each year on a nearby lake or stream, you likely know how sensitive this being is to disturbances like greatly fluctuating water levels, excess wave action, warming water temperatures, and increased frequency of historic floods. These factors and more have contributed heavily to the decline of healthy manoomin beds in the last several decades, and our continued stewardship requires us to keep very close observations on the plant itself, its lifecycle, and the water it grows in. It’s for this reason that Eric Greenlee, Computer Science PhD Student at Georgia Tech, is collaborating with GLIFWC, the Lac du Flambeau

Tribe, and the 1854 Treaty Authority to use modern technology to help bolster our understanding of manoomin waters. It comes in the form of sensor-containing buoys, bobbing on the edge of manoomin beds. They continuously collect data for water level, wave action, humidity, water and air temperature, and water and air pressure, all of which can be remotely viewed by the biologists in real time. Water quality and environmental stability are very important to the rice. These plants live out their entire lives in shallow, gently moving

waters in inland lakes and along the edges of rivers, growing in several distinct stages. Seeds begin their lives embedded in soft sediment after falling from their mother plant in late fall. They will lay dormant throughout the winter, and most will germinate the following spring, entering the submerged stage in which a root system and up to four small leaves will begin to form. These long leaves will gradually grow through the water column

to reach the surface, and by early summer, they will lay flat on top of the water. This is known as the “floating

leaf” stage and is where the plant is most vulnerable. Its buoyant leaves and underdeveloped root system allows it to be easily uprooted when the water is excessively disturbed, such as with high winds, flooding, or large

boat wakes, all of which has become more common with climate change and human recreation. By mid-summer, aerial shoots can be seen protruding from the water’s surface, beginning the emergent stage. By now, the roots have taken a stronger hold in the sediment, and the plant is less vulnerable to mild and moderate disturbances.

Over the next few months, these stalks will grow two to five feet above the water and will develop flowers, then seeds, and in early to mid-fall, harvesting will begin. This harvest is the gift given to us by the manoomin plant and the water it grows in. This is why the protection of the plant and the water is so important, and these specialized buoys offer a new way to collect crucial observations. This data will bring more understanding about the connections between human activities and manoomin, and it will help inform which acts of stewardship we need to prioritize, whether that’s educating about the effects of climate change or implementing more regulation such as no-wake zones. If you are out and about in Ceded Territory waters and come across any

of these buoys yourself, you will find contact information and a QR code. Visit www.manoom.in to learn more about the project.